The countries that contribute the least to climate change suffer the most devastating impacts. Climate reparations offer a path forward.

In 2022, Pakistan, a country responsible for less than one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, experienced some of the worst flooding in its history. The natural disaster cost 1,300 lives and put a third of the nation underwater. That same year, Somalia (0.03 percent of global carbon emissions) and Uganda (0.01 percent of global carbon emissions) dealt with a devastating drought that killed more than 45,000 people.

By 2050, if carbon emissions continue on their current trajectory, more than 143 million people will be driven from their homes by conflict over food and water insecurity and climate-driven natural disasters. By 2070, almost 20 percent of the planet could be too hot to be habitable. As a result of resource extraction, lack of investment, and generational poverty, the poorest and most vulnerable countries among us will shoulder the burdens of a hotter, more disaster-prone Earth. However, it’s the richest among us — like China and the United States, which contribute 30 percent and 15 percent of global carbon emissions, respectively — that have fueled the climate crisis.

That’s why climate reparations are essential. Climate reparations go beyond financial aid — although that’s a core component of the concept. The idea also includes a reparative and equitable approach to climate policy that addresses past and current injustices and offers a seat at the table for countries and communities that face unequal harm.

“Reparations are an opportunity to invest in reducing vulnerability — investing in more resilient infrastructure, providing communities and households with the financial resources to weather extreme events without succumbing to poverty,” says Manann Donoghoe, Senior Research Associate at the Brookings Institute and co-author of The Case For Climate Reparations in the United States. “With these goals, climate reparations could be an invaluable mechanism to fortify the most vulnerable nations to climate impacts in a way that can also increase their economic self-determination.”

Of course, the unequal impact of climate change isn’t confined to the international community — the same story is playing out in the U.S. In America, our country’s history of colonialism, slavery, environmental racism, and corporate greed puts predominantly Black and minority communities at greater risk of suffering the consequences of a warming planet.

For example, racist housing policies in the 1930s (also known as redlining), classified areas based on mortgage “risk level.” Often, majority Black and immigrant neighborhoods were labeled red, or high risk, as a way to deny them mortgage insurance and the ability to purchase property in low risk, mostly white areas. Today, due to continued lack of investment and a scarcity of tree cover and green spaces, formerly redlined areas still struggle economically and are as much as 13 degrees hotter than non-redlined communities. This fact is particularly consequential considering extreme heat kills more Americans per year than any other weather-related disaster.

Read more: How Urban Heat Islands Make Environmental Racism Worse

According to a 2021 analysis from the Environmental Protection Agency, Black Americans are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest increases in mortality rates due to climate-driven changes in extreme temperatures. Hispanic and Latino individuals are 43 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected labor hour losses due to climate-driven increases in high-temperature days and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals are 48 percent more likely live in areas where the highest percentage of land is projected to be inundated due to sea level rise.

“Some people tend to think of reparations as unnecessary navel gazing — dredging up a murky past. However, the impacts of colonialism on individuals, national economies, and the environment, is ongoing,” says Donoghoe. “And not just psychologically. Climate change is actually a great example of where reparations could have a positive impact because it makes clear just how much historic injustices are connected to present vulnerabilities. The decisions of nations, organizations, and corporations that exploited people and nations and contributed the most to global GHG emissions in the process have an obligation to act on these connections.”

When disaster hits, majority minority areas receive less recovery assistance than their white neighbors. For example, several studies show that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) does not distribute relief aid equitably. In fact, even when damage and loss is the same, Black households receive less government support due, in part, to biased housing appraisals which favor white homeowners.

Property values also don’t recover equally. After climate-related natural catastrophes, Black-majority communities experience a wealth decline of $27,000 while majority-white neighborhoods see property values increase by up to $126,000. It’s also more expensive for predominantly Black towns to borrow money in the first place, making it nearly impossible to build the economic prosperity and infrastructure essential to climate resilience.

“Marginalization starts with the idea that some people in the community are not true members. The people who believe they are the rightful proprietors of a place find ways to keep the marginalized from participating in governmental decision-making,” says Andre Perry, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute and co-author of The Case For Climate Reparations in The United States. “So, when the marginalized are negatively impacted by the lack of inclusion or the denial of access to basic goods and services, it’s very important they be given an opportunity to participate in their own recovery. The response to climate change isn’t simply a technical matter of reducing greenhouse emissions or creating more advanced renewable energies. The people who are most burdened by climate change must have a say in their own recovery as well as how we are to remove the conditions that led to their marginalization. If we don’t address these other community issues, we run the risk of repeating the core problem of not considering people as full-fledged members.”

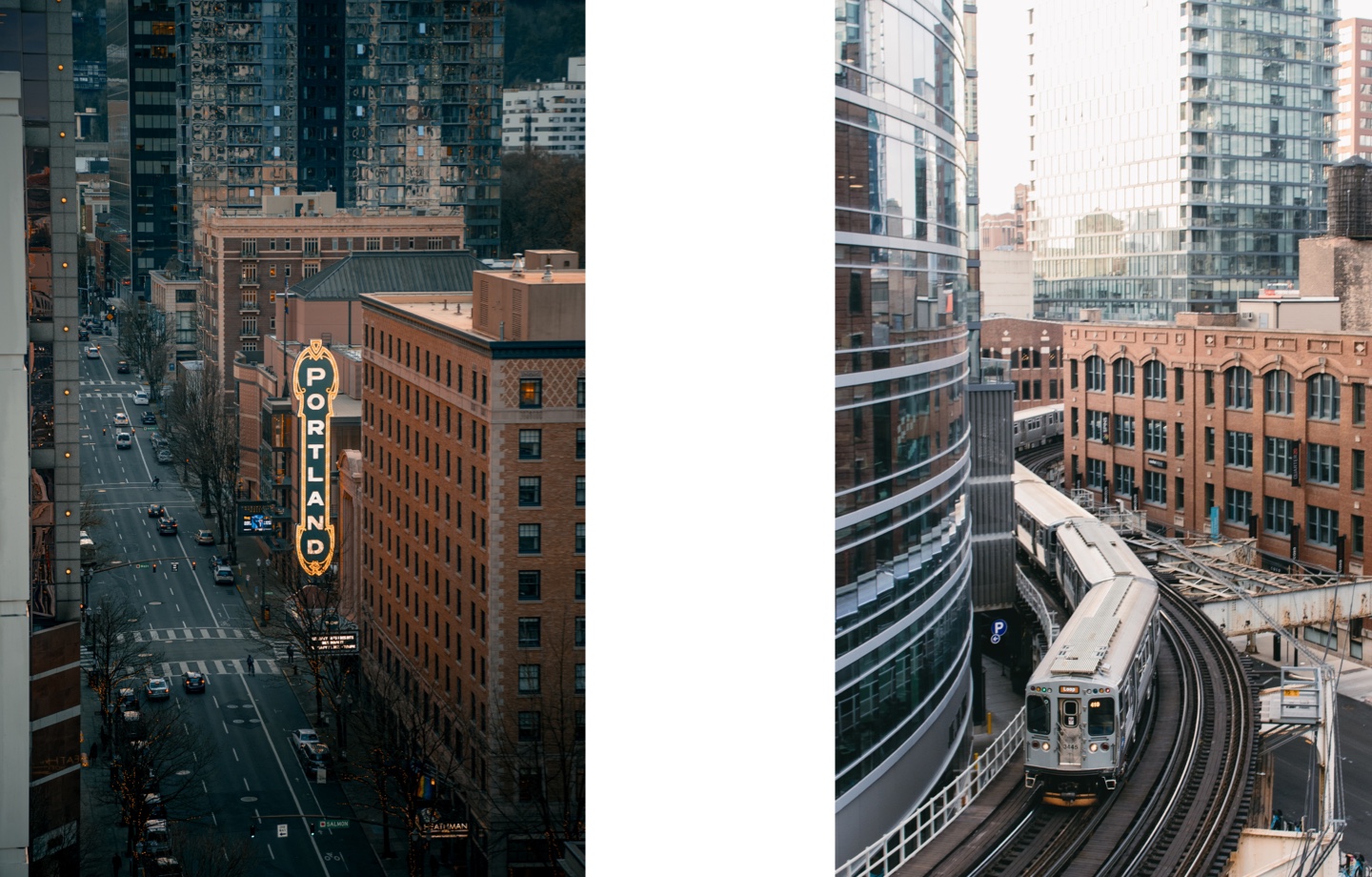

But there is hope for change — and signs that local governments are attempting to address the current and future consequences of environmental racism through reparative climate action. Earlier this year, Portland, Oregon, passed a Climate Investment Plan, which allocates funding for community-led climate projects that support the most impacted residents and prioritize racial, social, and economic justice benefits.

More recently, Minneapolis revised its Climate Action Plan to place environmental justice at the forefront. The new, 10-year Minneapolis Climate Equity Plan puts more focus on low-income and BIPOC areas and provides $8 to $10 million in annual funding to be used for green spaces in the north and south sides of Minneapolis. The plan will also fund air quality monitoring to track and reduce pollution and insulation and weatherization infrastructure for homes. The proposal also includes language guaranteeing low-income households won’t be hit with tax increases in the event of a funding shortfall.

And in Cicero, Illinois, a low-income suburb outside of Chicago that’s grappling with devastating floods due to increased heavy rainfall and sea level rise, programs like RainReady connect impacted community members with funding for flood prevention. The area is predominantly Latino and often overlooked and underserved when it comes to sustainability efforts and investment.

“The U.S. has an opportunity to lead here,” says Donoghoe. “By showing a progressive and forward-looking stance on climate reparations domestically, the U.S. could help to further the international case, promoting a more moral and collective action on climate change… It’s true that the idea of reparations makes people uncomfortable, and I think that’s because it involves facing up to aspects of our shared history that are difficult to confront: the exploitation of people, environmental destruction, enslavement. Reparations means reckoning with these histories.”

Have feedback on our story? Email [email protected] to let us know what you think!

Shop Pillows

The Essential Organic Pillow Collection

Gentle, breathable, non-toxic support.