In foraging invasive plants for edible, medicinal, and cosmetic purposes, a more ethical form of wildcrafting takes root in the American Southwest.

Richard Powers begins his novel The Overstory by recounting the life of one chestnut tree. That lone tree, planted by a Norwegian immigrant newly arrived in Iowa from Brooklyn in the 1800s, outlasts one generation after another of the immigrant’s family. Elsewhere, entire chestnut forests are felled by a fungus carried by the “invasive” ornamental Chinese Chestnut. This, “the most harvested tree in the country,” Powers writes, begins vanishing sometime around 1904 as a result. It’s a common tale. As species arrive in new places through the ebb and flow of globalization, native habitats, which have flourished in isolation, are disrupted or overcrowded — some to the point of extinction. According to the National Wildlife Federation, 42 percent of native species are threatened or endangered by those brought from elsewhere.

“Trying to support ecosystem balance without using harmful chemicals.”

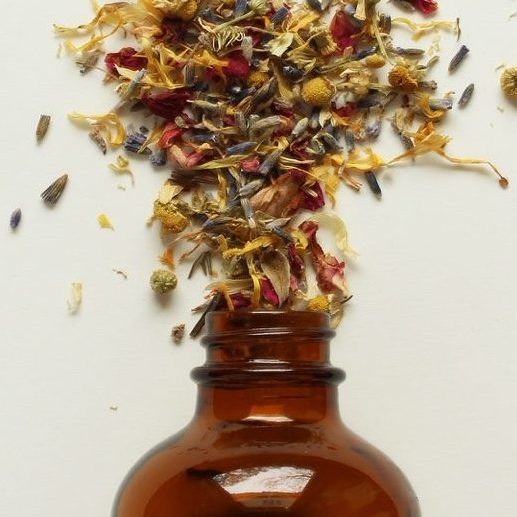

In the desert Southwest, Dryland Wilds prioritizes wildcrafting non-native plant species for their handcrafted soaps, balms, oils, and perfumes. Founded in 2016 by Robin Moore and

Wildcrafters have long foraged native plants from their natural, wild environments for edible, medicinal, or cosmetic purposes. For instance, indigenous peoples have dug the roots of osha, or bear root, from the subalpine areas of the Rocky Mountains for its curative properties. Ginseng, yarrow, rosehips, wild leeks, mushrooms, and sage, are just a handful of other popular wildcrafted plants. Yet, as with the overforaging of ginseng in Appalachia for a now massive export industry, or the endangerment of white sage when smudging became trendy in recent years, many wildcrafted plants are at risk of being overharvested.

As a result, there have been global calls for more ethical forms of wildcrafting, of which Robin Wall Kimmerer, scientist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, describes as the Honorable Harvest, or “a covenant of reciprocity between humans and the land.” Precepts, of which there are ten, include harvesting in a way that “minimizes harm,” and never taking the first of or the last of a specific plant. For Kimmerer, those precepts should hold true for the practice of wildcrafting as much as for land stewardship generally.

According to Dryland Wilds, wildcrafting non-native species is an important component of their own place-based ethics. For instance, Rose and Moore spent three years harvesting tens of thousands of Russian olive blossoms and laying them out in the time-consuming cold enfleurage process for their limited edition Rio Grande Spring perfume. Russian olive, while used medicinally in Iran, Turkey, and throughout Asia, has been considered a scourge for native vegetation in the Southwest. Once brought to North America as a windbreak, Russian olive now peppers the banks of the Rio Grande River, where bulldozers routinely attempt to rip it out. By setting up what they call “perfume camp” on sites like the Rio Grande Bosque, Dryland Wilds is able to reduce invasive seed set year after year.

Yet the question of just how invasive invasive species actually are in some environments is hardly cut and dry. In some cases, the fear around invasive species has been attributed to a general rhetoric of xenophobia, and also to industries that capitalize off of the manufacturing of herbicides.

“Whether we love or hate invasives, we’re also looking at what will survive climate change.”

Rose and Moore, who share a background in permaculture and also teach classes on wildcrafting, seek to understand invasives’ role in our ecosystems with the urgency of climate change in mind. After observing three years of major flooding, they realized it was the invasive species that remained resilient. “Whether we love or hate invasives, we’re also looking at what will survive climate change,” they said. Looking to the future also means asking in earnest “how will we be able to feed, heal, and take care of ourselves.” Invasives might hold one answer. Still, the balance of plants in any ecosystem, they believe, should always be “skewed back into native predominance.”

As for their other products, plant material “is salvaged from sites that are removing them for construction, road maintenance, land management, and fire pruning.” This work is less than romantic, they say, but it’s part of their own honorable harvest, in which the first step is always learning whose ancestral land we’re on and how it’s been stewarded.

Shop Pillows

The Essential Organic Pillow Collection

Gentle, breathable, non-toxic support.